We are well aware that plastic is starting to cover our planet at an alarming rate. Everything from plastic bags that hold our groceries to plastic bottles are filling up our landfills, polluting our oceans and even being burned and releasing toxic chemicals into our air.

Plastic takes a REAL LONG TIME to biodegrade

In our modern society plastic bottles are pretty much everywhere. They come from water bottles, reusable utensils, all the way to soda bottles. Every single year there are more and more of them that are filling up the landfills. How long does it really take for a normal plastic bottle to biodegrade?

We all know that all of the different kinds of plastics that are out there all degrade at different times, but the average time that it takes for a plastic bottle to completely degrade is at the least 450 years. Some bottles do not completely degrade for 1000 years!

To add to that, where you aware that 90% of all bottles made each year aren’t even recycled? Kind of makes you think twice about that soda or water bottle, doesn’t it? Finally, there are bottles that are made with Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET or PETE) which will never biodegrade.

About 1.5 million barrels of oil are used every year to make plastic bottles, and even more oil is burned transporting them. Most of the time, the water inside the bottles has more contaminants than regular old tap water, meaning you could be drinking some serious problems. The EPA has more strict standards on tap water than the FDA does for bottled water, which is something to think about when you’re thirsty! And those reusable bottles? Make sure you’re not a collector, because those will never biodegrade.

Plastic is finding its way into everything natural

Plastic is getting into everything. The global fishing industry dumps an estimated 150,000 tons of plastic into the oceans every year, that also includes plastic nets, packaging, buoys, and lines. An estimated 14 billion pounds of trash, which most of which is plastic, is dumped into the world’s oceans.

The North Pacific Gyre (The Great Pacific Garbage Patch)

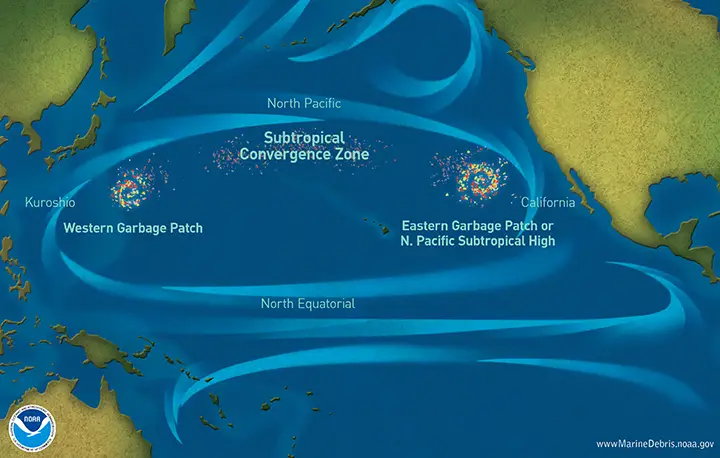

Yes, that’s right there is a Great Pacific Garbage Patch that has collected into a large mass that is located in the central North Pacific Ocean and is roughly between 135° to 155°W and 35° to 42°N.

There have been many scientists that have suggested that this enormous patch extends over an extremely wide area. The estimated ranges for the mass are from an area the size of Texas to one that is larger than the whole continental United States. In recent data that was collected from pacific albatross populations that strongly suggest that there may even be two distinct zones of this concentrated debris in the Pacific.

Recently a group of researchers discovered another major concern to our local water supplies and rivers: Microplastic.

Microplastics from Water Treatment Plants

There are actually millions of different tiny pieces of plastic that are escaping wastewater treatment plant filters and winding back into natural rivers where they could contaminate the food system and water supplies, according to the brand new research that is being presented here in this article.

What exactly are microplastics you might ask? Well, they are small pieces of plastic that are so small that they are less than 5 millimeters or (0.20 inches) wide. They are becoming a huge environmental concern in ocean waters, where they can damage the ecosystem to the point of also causing great harm to ocean animals. Not to mention that these plastics are also getting into freshwater rivers.

Rivers are the only source of drinking water for many communities and also creates habitats for wildlife. The microplastics are starting to enter into rivers and is affecting the river ecosystems, according to assistant professor from Loyola University Chicago, Timothy Hoellein. This plastic is being potentially eaten by fish and winding up in our bodies as well.

“Rivers have less water in them (than oceans), and we rely on that water much more intensely,” Hoellein said.

In a study, Hoellein and his team looked at 10 different urban rivers in the Illinois area. They found out that the water downstream from a wastewater treatment plant had a much higher concentration of these microplastics than water that was upstream from the plant.

The team’s initial estimates suggested that wastewater treatment plants are catching 90% or more of the incoming microplastics. The team found out that the amount of microplastics being released daily with treated wastewater into rivers is significant, ranging from 15,000 to 4.5 million particles per day, per treatment plant, according to the new research.

“[Wastewater treatment plants] do a great job of doing what they are designed to do — which is treat waste for major pathogens and remove excess chemicals like carbon and nitrogen from the water that is released back into the river,” Hoellein said. “But they weren’t designed to filter out these tiny particles.”

Hoellein said that he and his scientists are working hard to figure out just how much plastic staying in the rivers and how much of it ends up in the oceans. By studying microplastics in the rivers scientists could begin to better understand the entire lifecycle of these little microplastics.

“The study of microplastics shouldn’t be separated by an artificial disciplinary boundary,” he said. “These aquatic ecosystems are all connected.”

It seems that so much of our trash still ends up in the oceans and rivers of our world. To some people, it may be too hard to make a conscious shift to being more aware of where our waste goes and how to make less of it. So with that being said it seems that if we continue down the path we are on with how we handle plastic bottles and other trash then all of our fresh clean sources of water will all be contaminated.

What did you think about this topic? Leave us a comment and join the discussion below.

Sources–

Image Source- capitalwired.com