Science & Tech

Scientists Are About to Bring This Extinct Australian Animal Back to Life

What could possibly go wrong?

It has been almost a century since the Tasmanian tiger was last spotted, but there is new hope that the extinct animal will thrive once again in the near future.

The striped carnivorous marsupial known as a thylacine, which used to roam the Australian wilderness, is one of the extinct animals that scientists are hoping to bring back to life.

It’s safe to say the character Ian Malcolm from Jurassic Park would be quite unhappy.

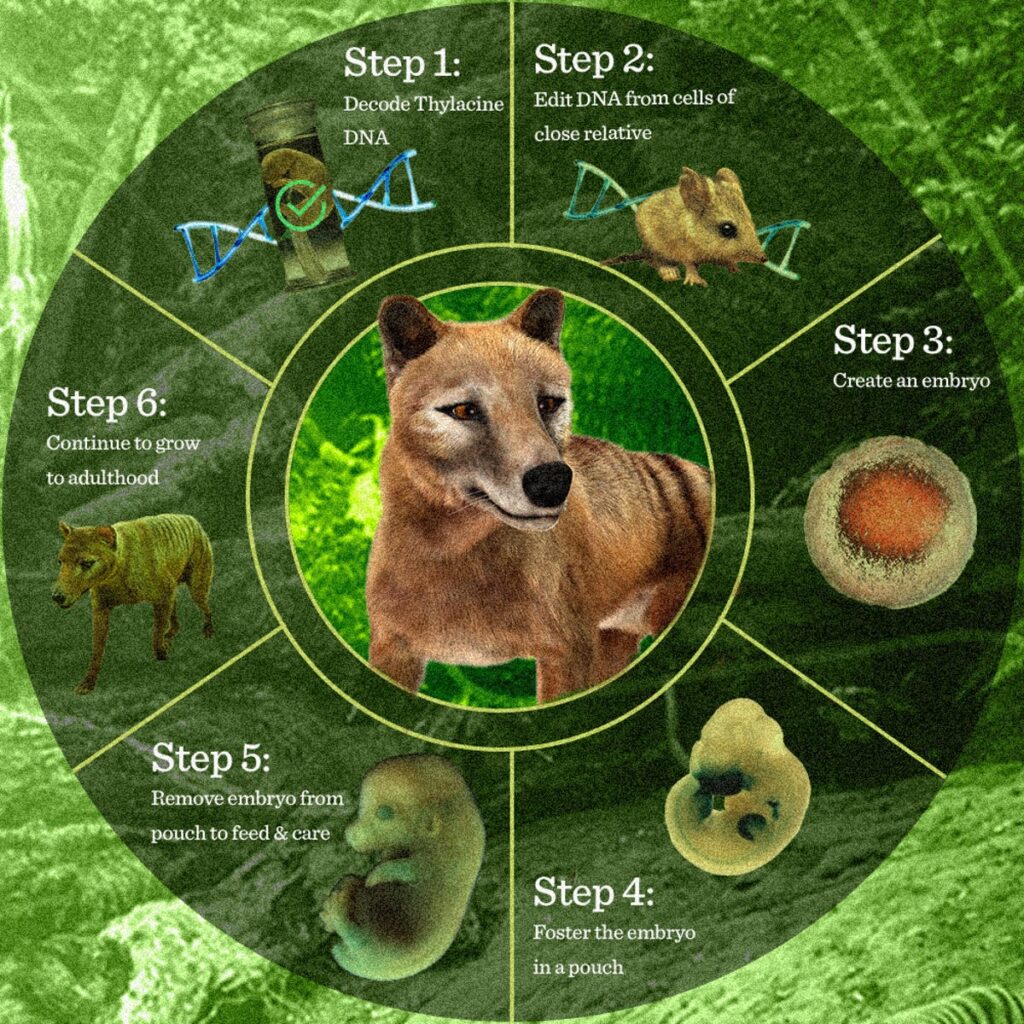

The “de-extinction” U.S. biotech company Colossal Biosciences plans to use gene-editing technology to resurrect the extinct animal, an ambitious endeavor that will utilize the retrieval of ancient DNA and the manufacture of artificial offspring.

“We would strongly advocate that first and foremost we need to protect our biodiversity from further extinctions, but unfortunately we are not seeing a slowing down in species loss,” said Andrew Pask, a professor of evolutionary biology at the University of Melbourne who has collaborated with Colossal Biosciences.

“This technology offers a chance to correct this and could be applied in exceptional circumstances where cornerstone species have been lost,” he added.

This is not the first time that Colossal has made it known that they wish to bring back an extinct animal. The idea to bring woolly mammoths back into existence by the year 2027 was announced to the world by Colossal last year.

In contrast to mammoths, the Tasmanian tiger cannot point the finger of blame at natural processes for its demise. The animal’s extinction can be attributed in large part to hunting by humans.

However it was Willy Batty, a farmer in Australia, who killed the last known thylacine in 1930. He did it to protect his chickens from being eaten by the animal.

Even though their name suggests otherwise, Tasmanian tigers are actually marsupials, regardless of the fact that they appear to be a hybrid of a wild dog and a wild cat.

Professor Pask has made it abundantly clear that the objective is not to bring back the Tasmanian tiger as purely a scientific experiment but rather for the long term so that it can be reintroduced into the wild.

According to Pask, “To bring a healthy population of thylacines back, you can’t bring back one or five.”

“You’re looking at bringing back a good number of animals that you can put back into the environment,” he added.

The entire concept of bringing back extinct species is fraught with controversy in the scientific world, particularly due to the possible ethical repercussions that could result.

What if efforts to reintroduce species, such as the Tasmanian tiger, just result in their extinction once more? In what ways will the restoration of these animals into their natural habitat affect the native people who live there? Is it realistic for us to hope to forecast how well they will do, as well as how well other species will do when they come back?

Additionally, conservationists are concerned that if de-extinction becomes popular, it will divert resources away from the protection of species that we are still actually able to preserve.

More than 30 scientists collaborated on the research with the goal of accelerating the “huge grand challenge” of bringing the Tasmanian tiger back from the dead. According to Pask, the effort was the single most important contribution ever made to marsupial conservation in Australia.

He believes that the first joeys will be born in ten years.

Ben Lamm, the chief executive and other co-founder of Colossal, is even more optimistic and believes it will be possible to produce the first set of mammoth calves in less than six years.

“I think it’s highly probable this could be the first animal we de-extinct,” Lamm told the Guardian.

According to Pask, the rate at which the world is changing is too fast for the methods of conservation currently in use to preserve many endangered species, citing the devastating impact that bushfires have had on Australian animals.

If we want to put a stop to the loss of biodiversity, Pask explained: “We have to look at other technologies and novel ways to do that if we want to stop this biodiversity loss.”

“We have no choice. I mean, it will lead to our own extinction if we lose 50% of biodiversity on Earth in the next 50 to 100 years,” he added.

Typos, corrections and/or news tips? Email us at Contact@TheMindUnleashed.com