Science & Tech

The Mandela Effect is Real, Scientists Confirm in a New Study

However, they are unable to provide a single explanation for the strange phenomenon.

The Mandela Effect, which refers to a persistent, confident, and widespread false memory, has been proven to exist with famous icons, scientists have confirmed in a new study, which is available in preprint and forthcoming in the journal Psychological Science.

The research shows a consistent pattern in both what people remember and what they get wrong. According to scholars from the University of Chicago, this is the first scientific investigation of the internet phenomenon.

Humans are confident in what they remember. We’re also consistently wrong about what we think we remember, and yet it doesn’t seem to alter beliefs.

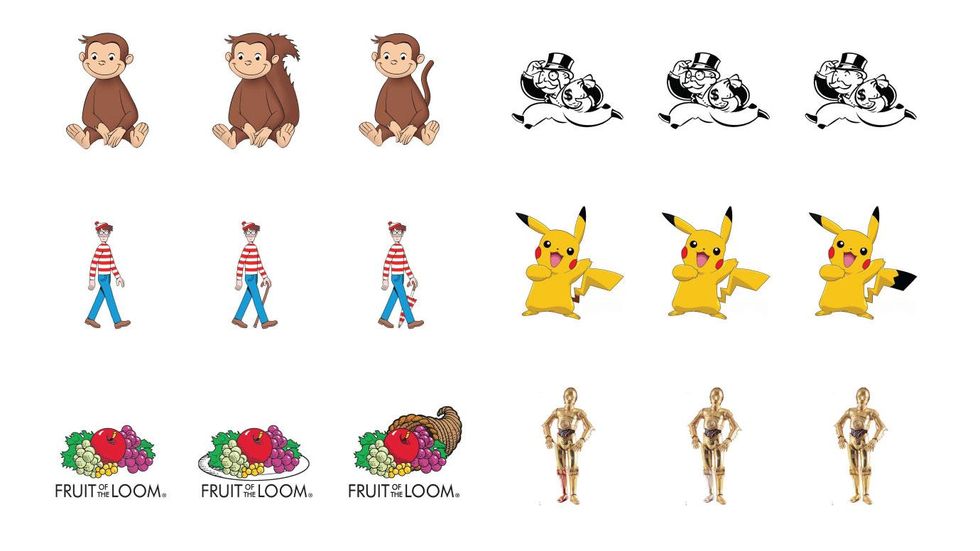

Exhibit A: Choose the appropriate logo or character from the image below.

If you get any wrong, congratulations! You’ve just experienced the internet phenomenon known as the Mandela Effect—a persistent, confident, and widespread false memory.

It bears Nelson Mandela’s name, the first president of South Africa and a leading opponent of apartheid. Mandela didn’t pass away until 2013, but many people believe he actually died in prison during the 1980s because that’s what they think they remember.

The Mandela Effect took an unexpected turn when a pair of University of Chicago scholars recently completed the world’s first scientific study of the phenomenon. What they discovered confirms the idea that there’s a consistency in the things people misremember.

“This effect is really fascinating because it reveals that there are these consistencies across people in false memories that they have for images they’ve actually never seen,” said Wilma Bainbridge, one of the authors of the new paper and an assistant professor at the University of Chicago’s Department of Psychology.

The researchers gathered forty popular culture emblems and icons and then added two fictitious counterparts to each of them. As motivation, they utilized online discussions of the Mandela Effect.

In order to better test their beliefs, the researchers frequently altered one of the two incorrect options such that it was no longer related to what was most frequently forgotten.

They wanted to determine how widespread and consistent the Mandela Effect was as well as search for the underlying causes. In order to do this, they quantified how common the false memory images were in the world and conducted experiments to determine whether or not people produce the errors on their own.

For instance, if individuals are asked to draw an image from memory, are they prone to the same kinds of mistakes that they do when selecting the correct logo based on recognition?

“We found that there really is a strong effect where people are reporting a false memory for an image they actually have never seen—because you’ve never seen Pikachu with a black tip on the tail,” Bainbridge explained.

“What’s more is that people tend to be very confident in picking this wrong image. And they also report that they’re pretty familiar with characters like Pikachu, yet they still make these errors,” she added.

The researchers are unable to provide an explanation for the phenomenon; nonetheless, they have ruled out other potential explanations.

First, they don’t believe that individuals are looking at images in a different way since they find that people are more likely to choose the incorrect option even when they are looking at the correct version. In addition, they do not believe that we are only filling in information that is lacking based on the associations we have, which is a notion that is known as schema theory.

Unfortunately, the researchers aren’t getting any closer to discovering the real causes behind the Mandela Effect by ruling out some of the possibilities.

“You would think that because all of us have our own individual experiences throughout our lives that we’d all have these idiosyncratic differences in our memories,” Bainbridge said.

“But surprisingly, we find that we tend to remember the same faces and pictures as each other. This consistency in our memories is really powerful, because this means that I can know how memorable certain pictures are, I could quantify it. I could even manipulate the memorability of an image.”

This then leads to the concept of controlling the production of false memories, which, according to Bainbridge, has interesting ramifications in terms of the design of logos, photo selections for advertisements, and how we recall educational content.

“You don’t want them to misremember information,” she explained. “And that actually relates a lot to some other important topics right now, including what images are used in the media.”

Answers:

- Curious George: Left (no tail)

- Where’s Waldo: Center (holding cane)

- Fruit of the Loom: Left (no plate or cornucopia)

- Mr. Monopoly: Right (no glasses or monocle)

- Pikachu: Left (brown coloring at base of tail)

- C-3PO: Center (silver leg)

Typos, corrections and/or news tips? Email us at Contact@TheMindUnleashed.com