Consciousness

4 Zen Koans That Reveal Startling Wisdom

A Zen koan is a finger pointing at the moon. It isn’t meant to serve up absolute truth on a platter, but to help a seeker contemplate the wisdom behind its riddle. A koan, or a puzzle for the consciousness, should instill ‘great doubt’ about a subject, so that students, especially of the Renzai tradition, can test their progress toward awakening. Seeking the ‘selfless self,’ as a way to clarify the Great Way has been passed down for centuries by Zen masters, but this practice is still useful today.

Before getting to ‘work’ on a koan, or the mental conundrum that is offered as a way to enlightenment, we can take the advice of Zen master, Wumen Huikai (Mumon Ekai, 1183-1260), who explains in detail from his own experience in his book, The Gateless Barrier (in Japanese, Mumonkan),

“In brief, the important thing is not to think about the koan with one’s mind, but to become it by unreservedly devoting one’s whole body and mind to it.”

In other words, we can’t use the same mind to solve a problem as the mind that created it – the same old Einsteinian wisdom that can be applied so completely to what the world is going through today.

So, let’s begin.

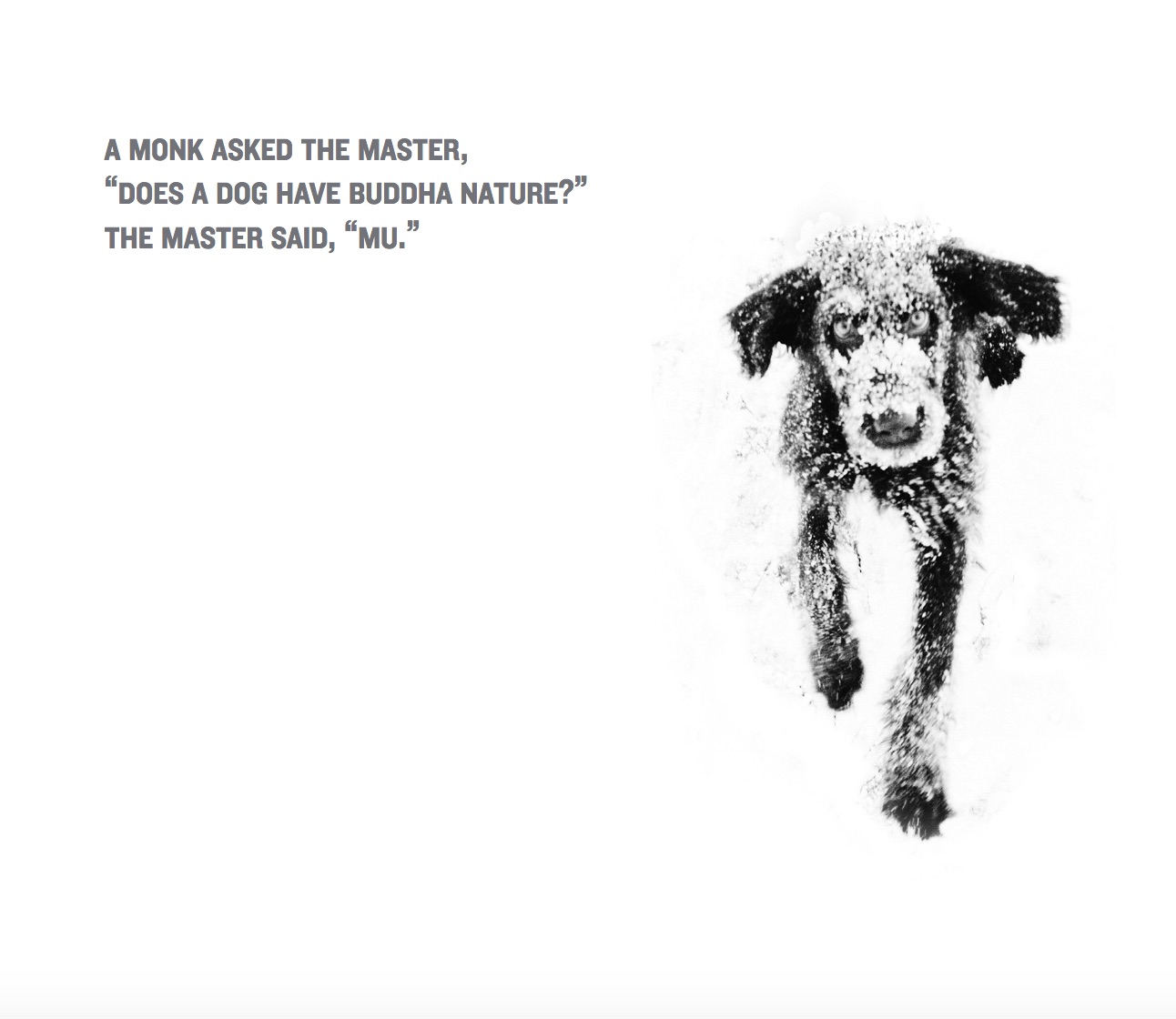

The first Zen koan reminds us that every single person can arrive at the Great Way, or experience “Mu,” a shorthand word for the very first koan ever written, which supposedly contains the secrets of the Gateless Gate. Mu helps us break through the conceptual fog that many of us live in.

This koan, titled Washing the Bowl is about eliminating the habits of procrastination, a key task if we are to obtain Mu. It goes like this:

A monk told Joshua: “I have just entered the monastery. Please teach me.”

Joshua asked: “Have you eaten your rice porridge?”

The monk replied: “I have eaten.”

Joshua said: “Then you had better wash your bowl.”

At that moment the monk was enlightened.

There are many ways to arrive at the answer to this riddle, but essentially it outlines the need to get started on something right away, and not to wait to take care of the things that need to be done. You don’t wait until later, or tomorrow, or next week. You eat. You finish. You wash your bowl. All great things are accomplished with this attitude of immediacy. Otherwise, the dirty bowls pile up, and no one attains enlightenment with clutter choking their space.

Procrastination is a habit many of us struggle with. We have all sorts of crutches that keep us from getting to the things that really matter. Is there something you could be doing with your time to become more loving, peaceful, or productive that is wasted by watching television, smoking, drinking, playing video games, surfing the net, or some other bad habit? False ‘needs,’ like the need to smoke or drink inhibit our ability to act on the important stuff. As we learn to let go of these things, we can ‘wash the bowl’ more often.

The next koan is about desire:

“Mountains are not mountains. Mountains are mountains.”

Let’s say we want to climb a mountain. We set this as our ideal. There is a paradox in desire, though. With most things in life, we set something as our goal, and consciously work very hard to achieve it. If our aim is to free ourselves of desire though, how do we accomplish this task? In the process of intensely desiring not to desire, we set up an unsolvable problem of not being able to attain our goal.

There is a story about a Zen student who arrives at a temple and finds an audience with a Zen master. He asks the master how long it will take him to become enlightened. The master tells him, “ten years.” With this answer the seeker says to the master, “If I work very hard to achieve enlightenment, how long will it take?” The master’s response is, “twenty years.”

Most of out troubles arise from clinging too tightly to any goal – even the most noble of them. The story points to the need to radically change our approach if we are to overcome desire. The mountain is the mountain, but it isn’t a mountain. We practice loving detachment, and strangely, we are able to let go of clinging to things as we want them to be. Paradoxically, we often also achieve the goal we originally had to let go of in the process of becoming desireless, and letting go of our attachments.

The next Zen koan involves what seems to be a silly question. It asks if all beings have ‘Buddha nature.’ Zen, and Mahayana Buddhists believe that all things have Buddha nature, even insects. The seed of enlightened consciousness is in every living thing. The choice for that being to move toward enlightenment is entirely theirs, though. This, in fact, could be more important than ‘if’ someone or something has Buddha nature, since we all do, but whether or not they will endeavor to realize it in its full blossoming.

There is a story of a brahman (a seeker) who asked the Buddha if all the world would reach release [awakening], or if half, a third, or some other number would achieve this. The Buddha was silent. One of the Buddha’s attendants, worried that the brahman might confuse the Buddha’s answer, took him aside and offered an analogy. He said, “Imagine a fortress with a single gate. A wise gatekeeper would walk around the fortress and not see an opening in the wall big enough for even a cat to slip through. Because he’s wise, he would realize that his knowledge didn’t tell him how many people would come into the fortress, but it did tell him that whoever came into the fortress would have to come in through the gate.” The enlightened ones, such as the Buddha didn’t worry about how many people would reach Awakening, but he understood that anyone who reached this high state of consciousness would have to follow the path he had found: abandoning the five hindrances, establishing the four frames of reference, and developing the seven factors for Awakening. Though these are detailed very specifically in Buddhism, they are echoed through almost every wisdom tradition in the world.

The most important point of the koan is implied in the word ‘if.’ The path is clearly defined, but the choice lies with the sentient being if they want to realize Mu or Satori.

The fourth zen koan is not a verbal puzzle but a visual puzzle. The ensō or circle symbolizes absolute enlightenment, strength, elegance, the universe, and mu (the void). The circle encompasses all and excludes nothing. Contemplate on this symbol, and share what wisdom it brings to you.

The fourth zen koan is not a verbal puzzle but a visual puzzle. The ensō or circle symbolizes absolute enlightenment, strength, elegance, the universe, and mu (the void). The circle encompasses all and excludes nothing. Contemplate on this symbol, and share what wisdom it brings to you.

Image credits: WisdomPubs.org, Ericgerlachdtocom, EddieTwoHawks, Float Universe, BuddhistChannel.tv, Dailycupofyoga.com

Awareness

Bleeding Eye’ Virus Sparks Travel Warning and Worldwide Concern – What Is the Incurable Disease?

A mysterious and deadly virus is capturing global attention, sparking urgent travel warnings and widespread concern. Known for its unsettling nickname—the “Bleeding Eye” virus—this disease has not only shaken the health sector but also left travelers and governments on high alert. Its symptoms are as alarming as its name, and its impact has already been felt in multiple regions.

What is this incurable disease that has the world watching so closely? How did it emerge, and why is it spreading so rapidly?

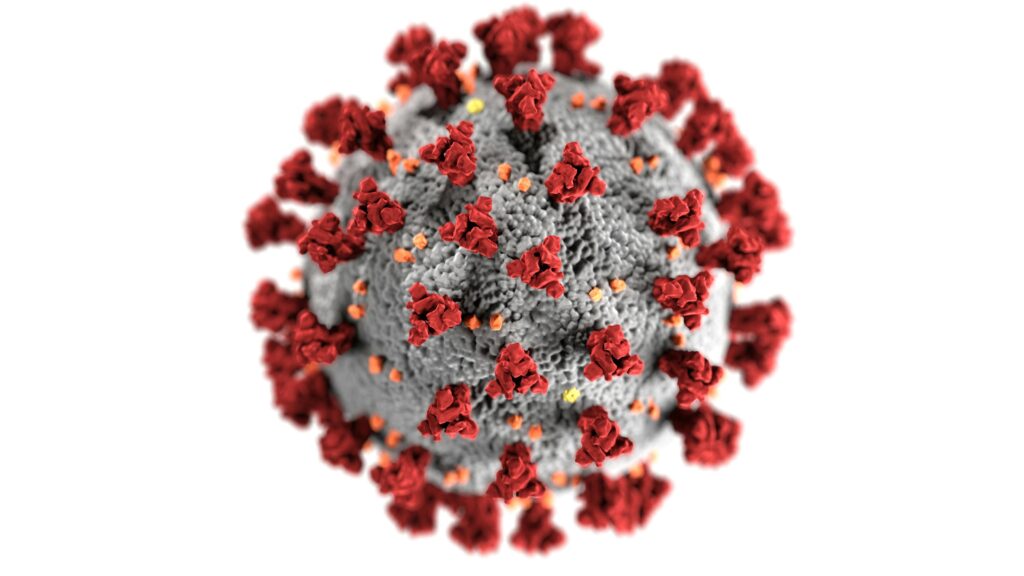

What Is the Marburg Virus?

The Marburg virus, a member of the Filoviridae family, is a highly virulent pathogen responsible for Marburg virus disease (MVD), a severe hemorrhagic fever in humans. First identified in 1967 during simultaneous outbreaks in Marburg and Frankfurt, Germany, and Belgrade, Serbia, the virus was traced back to African green monkeys imported from Uganda for research purposes. This initial outbreak resulted in several fatalities among laboratory workers, marking the virus’s alarming entry into the human population.

Marburg virus is closely related to the Ebola virus, sharing similar structural characteristics and disease manifestations. Both viruses are filamentous and contain single-stranded RNA genomes, leading to severe hemorrhagic fevers with high mortality rates. The natural reservoir for the Marburg virus is the Egyptian fruit bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus), with human infections typically resulting from prolonged exposure to mines or caves inhabited by these bats.

Transmission to humans occurs through direct contact with the blood, secretions, organs, or other bodily fluids of infected individuals or animals. Human-to-human transmission is facilitated by direct contact with broken skin or mucous membranes, as well as contact with surfaces and materials contaminated with these fluids, such as bedding and clothing.

The incubation period for MVD ranges from 2 to 21 days, after which symptoms such as high fever, severe headache, muscle pains, and profound weakness abruptly manifest. As the disease progresses, patients may experience severe hemorrhagic manifestations, including bleeding from the nose, gums, and eyes, leading to the virus’s colloquial name, the “bleeding eye” virus. The World Health Organization notes that the average case fatality rate for MVD is around 50%, with rates varying from 24% to 88% in past outbreaks, depending on virus strain and case management.

Currently, there are no approved vaccines or antiviral treatments for MVD. However, early supportive care with rehydration and symptomatic treatment significantly improves survival rates. Ongoing research aims to develop effective vaccines and therapeutics to combat this deadly virus.

Symptoms and Progression of Marburg Virus Disease

Marburg virus disease (MVD) is a severe and often fatal illness characterized by a rapid onset of symptoms that can escalate swiftly. Understanding the progression of these symptoms is crucial for early detection and improving survival rates.

- Incubation Period: The incubation period for MVD ranges from 2 to 21 days, with symptoms typically appearing abruptly.

- Initial Symptoms: The disease begins suddenly with high fever, severe headache, and malaise. Muscle aches and pains are common.

- Gastrointestinal Phase: By the third day, patients may experience severe watery diarrhea, abdominal pain and cramping, nausea, and vomiting. This phase can last for a week, and patients have been described as having “ghost-like” drawn features, deep-set eyes, expressionless faces, and extreme lethargy.

- Hemorrhagic Manifestations: Between days 5 and 7, hemorrhagic symptoms may develop, including:

- Bleeding from the nose, gums, and injection sites

- Blood in vomit and feces

- Spontaneous bleeding from the eyes, leading to the “bleeding eye” nickname

- Notably, “because it’s hemorrhagic, it ‘damages blood vessels and causes bleeding’ — often from the eyes, nose, mouth, or vagina.”

- Neurological Symptoms:

- In later stages, patients may exhibit neurological symptoms such as confusion, irritability, and aggression.

- Fatal Outcomes:

- In fatal cases, death usually occurs between 8 and 9 days after symptom onset, often preceded by severe blood loss and shock.

- Recovery Phase: Survivors may face a prolonged recovery, with symptoms like:

- Myalgia

- Hepatitis

- Weakness

- Ocular issues

- Psychosis

These symptoms can persist for weeks or months.

Transmission of Marburg Virus Disease

Marburg virus disease (MVD) is a highly virulent illness transmitted to humans through specific interactions with infected animals and individuals. Understanding these transmission pathways is crucial for implementing effective preventive measures.

Primary Transmission: Animal to Human

- Natural Reservoir: The primary hosts of the Marburg virus are fruit bats, specifically Rousettus aegyptiacus. These bats harbor the virus without exhibiting symptoms, facilitating its persistence in nature.

- Zoonotic Spillover: Human infections occur through direct exposure to infected bats or their excretions. Activities such as visiting or working in caves inhabited by bat colonies or handling bushmeat can lead to transmission.

Secondary Transmission: Human to Human

- Direct Contact: The virus spreads between humans via direct contact with the blood, secretions, organs, or other bodily fluids of infected individuals. This includes exposure through broken skin or mucous membranes.

- Contaminated Surfaces: Contact with surfaces and materials (e.g., bedding, clothing) contaminated with these fluids can also facilitate transmission.

- Healthcare Settings: Healthcare workers have been infected while treating patients with suspected or confirmed MVD, underscoring the importance of strict infection control measures.

- Burial Practices: Traditional burial ceremonies that involve direct contact with the body of the deceased can contribute to the transmission of Marburg virus.

Additional Considerations

- Sexual Transmission: Marburg virus transmission via infected semen has been documented up to seven weeks after clinical recovery, indicating that sexual transmission is possible during the convalescent phase.

- Nosocomial Transmission: Inadequate use of personal protective equipment (PPE) in healthcare settings can lead to nosocomial transmission, emphasizing the need for proper PPE protocols.

Recent Outbreaks and Affected Regions

Marburg virus disease (MVD) has reemerged in various regions, prompting significant health concerns. Notably, in September 2024, Rwanda reported its first-ever outbreak of MVD, with 66 confirmed cases and 15 deaths as of November 8, 2024. The outbreak primarily affected healthcare workers, especially those in intensive care units, across seven districts, including Gasabo, Kicukiro, and Nyarugenge in Kigali Province.

Earlier, in March 2023, Tanzania experienced its inaugural MVD outbreak in the Kagera region, resulting in nine cases and six deaths. This outbreak was contained by June 2023.

These incidents underscore the virus’s potential to spread across borders, especially in regions with close human and animal interactions. The World Health Organization (WHO) has been actively involved in supporting affected countries to implement control measures and prevent further transmission.

Global Response and Travel Warnings

The recent outbreak of Marburg virus disease (MVD) in Rwanda has prompted a coordinated international response to prevent further spread. As of November 8, 2024, Rwanda reported 66 confirmed cases and 15 deaths, with healthcare workers being significantly affected.

World Health Organization (WHO) Actions

The WHO has been actively involved in supporting Rwanda’s efforts to control the outbreak. On November 9, 2024, the WHO announced the commencement of a 42-day countdown to declare the end of the outbreak, following the discharge of the last confirmed patient. The organization continues to assist in surveillance and infection prevention measures.

Travel Advisories

In response to the outbreak, various health agencies have issued travel advisories:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): The CDC updated its interim recommendations for public health management of travelers arriving in the United States from Rwanda, reflecting the current status of the outbreak.

- Travel Health Pro (UK): Travel Health Pro, associated with the UK Health Security Agency, advised travelers to exercise caution due to the spread of Marburg virus, Mpox, and Oropouche fever in multiple countries, including Rwanda.

Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) Statement

The Africa CDC urged countries to avoid implementing travel bans or movement restrictions targeting African nations, emphasizing that such measures are inconsistent with international health guidelines and could hinder public health efforts.

Preventive Measures

Travelers to affected regions are advised to:

- Avoid Contact with Bats and Non-Human Primates: As these animals are natural reservoirs of the virus.

- Practice Good Hygiene: Regular handwashing with soap and water.

- Seek Medical Advice: Consult healthcare providers before traveling to outbreak areas.

These measures are crucial in preventing the spread of MVD and ensuring public health safety.

Preventive Measures Against Marburg Virus Disease

Marburg Virus Disease (MVD) is a severe and often fatal illness with no approved vaccines or antiviral treatments currently available. Therefore, implementing effective preventive measures is crucial to control its spread.

1. Avoid Contact with Potential Animal Hosts

- Fruit Bats: The Rousettus aegyptiacus fruit bat is identified as the natural reservoir for the Marburg virus. Avoiding contact with these bats, especially in caves or mines where they reside, can reduce the risk of transmission.

- Non-Human Primates: Refrain from handling or consuming bushmeat from non-human primates, as they can be carriers of the virus.

2. Implement Strict Infection Control Practices

- Healthcare Settings: Healthcare workers should adhere to stringent infection prevention and control measures, including the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) such as gloves, masks, gowns, and eye protection, to prevent contact with patients’ blood and body fluids.

- Isolation of Infected Individuals: Prompt isolation of suspected or confirmed MVD cases is essential to prevent nosocomial transmission.

3. Practice Good Hygiene

- Hand Hygiene: Regular handwashing with soap and water or using alcohol-based hand sanitizers can reduce the risk of transmission.

- Avoid Contact with Infected Individuals: Minimize direct contact with individuals showing symptoms of MVD and their belongings.

4. Safe Burial Practices

- Handling of Deceased Bodies: Traditional burial practices that involve direct contact with the deceased should be modified to prevent transmission. Engaging trained personnel to handle burials safely is recommended.

5. Community Engagement and Education

- Awareness Campaigns: Educating communities about MVD transmission and prevention strategies is vital for controlling outbreaks.

- Reporting Suspected Cases: Encouraging prompt reporting of suspected MVD cases to health authorities facilitates timely response and containment.

Staying Vigilant Against the Marburg Threat

The Marburg virus, with its devastating impact and high mortality rate, remains a pressing global health concern. From its alarming symptoms to its rapid transmission, understanding this disease is vital for prevention and containment. While recent outbreaks have highlighted the challenges in managing this deadly virus, they have also spurred coordinated international efforts to enhance surveillance, enforce preventive measures, and develop potential treatments.

Staying informed, practicing good hygiene, and adhering to travel advisories are essential for mitigating risks, especially for those in or traveling to affected regions. By prioritizing education and vigilance, we can collectively work toward minimizing the spread of the Marburg virus and safeguarding public health.

Consciousness

Top 10 Mental Health Myths You Need to Stop Believing

In a world where mental health awareness is on the rise, myths and misunderstandings still linger, shaping perceptions in ways that can be harmful and misleading. Many of us have likely encountered some common phrases like, “People with mental health issues just need to toughen up,” or “Therapy is only for those who can’t handle life.” But are these beliefs really rooted in fact, or are they products of outdated thinking and misconceptions?

Myth 1: Mental Health Problems Are Rare

Mental health challenges aren’t as rare as some might think—they affect a huge portion of the global population. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “1 in 4 people in the world will be affected by mental or neurological disorders at some point in their lives.” In the United States, more than one in five adults live with a mental illness, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). This prevalence shows how common mental health issues are and underscores the need to recognize and address them as a regular part of health.

The COVID-19 pandemic has only intensified mental health struggles. A study published in JAMA Network Open found that the number of adults experiencing depression in the U.S. tripled during the pandemic, highlighting the importance of increased mental health support, especially during times of global crisis.

Understanding how common mental health issues are is key to fighting stigma and helping people feel comfortable seeking support. Realizing that these challenges affect many can foster a more supportive and empathetic society.

Myth 2: People with Mental Health Issues Are Weak

The idea that mental health struggles reflect personal weakness is a harmful misconception. Mental health conditions are complex medical issues, influenced by a mix of genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors—none of which reflect on an individual’s character or strength.

The South Australian Health Department states, “A mental illness is not a character flaw. It is caused by a complex interplay of genetic, biological, social and environmental factors.” This underscores that mental health issues are not personal shortcomings but multifaceted health conditions.

NAMI also emphasizes that mental health conditions “have nothing to do with being lazy or weak, and many people need help to get better.” Seeking help is actually a proactive and courageous step, not a sign of weakness. It takes resilience and strength to confront these challenges, engage in treatment, and work toward recovery.

In reality, managing a mental health condition often requires significant courage. People facing these challenges show immense strength by seeking treatment and committing to recovery. As many say, “Fighting a mental health condition takes a great deal of strength”—a perspective that recognizes the resilience required to manage these struggles.

Myth 3: Therapy is Only for “Crazy” People

There’s this idea out there that therapy is only for people dealing with serious mental illness, but that’s a huge misconception. Therapy can actually help with all kinds of things—from handling everyday stress to working on personal growth and navigating life’s ups and downs.

Think of therapy as a safe, private place where you can talk openly with someone who’s trained to really listen and guide you. It’s different from venting to friends or family. Therapists have tools and techniques they’re trained to use that can genuinely make a difference.

And science backs this up. For example, research in the Journal of Counseling Psychology found that people who go to therapy report feeling better and handling life’s challenges more easily.

The truth is, therapy isn’t just for people in crisis. Lots of folks go to work on self-awareness, strengthen their relationships, or just set themselves up to live a fuller life. Let’s get rid of the idea that therapy is only for people with “serious” issues. It’s a helpful resource for anyone looking to feel better and grow.

Myth 4: Mental Health Conditions Are Permanent

A lot of people think that if you’re diagnosed with a mental health condition, you’re stuck with it forever. But that’s not always the case—plenty of people see real improvement, and some even recover fully.

Mental health isn’t a one-size-fits-all kind of thing. Recovery looks different for everyone, and things like getting help early, finding the right treatment, and making lifestyle changes can make a huge difference. The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) even says, “recovery is a process, and it’s possible for people to recover and live full and productive lives.”

There’s research to back this up, too. One study in Psychiatric Services found that people dealing with serious mental health challenges saw big improvements in their lives when they had solid, community-based support.

Recovery might mean different things to different people. For some, it’s learning how to manage symptoms so they can live well. For others, it’s about reaching a point where symptoms are no longer an issue. Either way, mental health challenges don’t have to be a lifelong roadblock. Improvement is possible, and with the right help, people can and do live fulfilling lives.

Myth 5: People with Mental Health Disorders Are Violent

There’s this stereotype that people with mental health issues are violent, but it’s just not true. Most people dealing with mental health challenges aren’t violent at all—in fact, they’re often more likely to be victims of violence rather than the ones causing it.

Studies show that mental health issues alone don’t make someone violent. A big review done in 2015 found that only about 4% of violent acts in the U.S. could be linked to people with mental health disorders. So blaming mental illness for violent behavior doesn’t really add up and actually creates a lot of unfair stigma.

Plus, people with severe mental health conditions are actually at a higher risk of getting hurt themselves. Research has shown they’re more likely to be victims of violent crime compared to the general population.

It’s also worth remembering that things like drug or alcohol use, financial issues, and personal history are way bigger factors in violent behavior than mental health. Breaking down this myth is important to help reduce stigma and build a more accurate, compassionate understanding of mental health.

Myth 6: Mental Health Issues Are a Sign of Weakness

A lot of people still think that mental health struggles mean a person is weak or lacks willpower. But honestly, mental health has nothing to do with being “tough” or “weak.” Mental health conditions are just as real as physical ones, and they happen because of a whole mix of factors—genetics, environment, biology, you name it.

Imagine telling someone with a broken leg to just “toughen up” and walk it off. It sounds silly, right? Yet people say things like this about mental health all the time. Groups like the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) are clear about it: mental health issues aren’t caused by a lack of character or inner strength.

Truth is, facing a mental health challenge actually takes a lot of strength. It’s not easy to ask for help, stick to treatment, and keep going, especially when things get tough. People dealing with mental health issues are often some of the strongest out there—they’re just dealing with a different kind of battle.

So let’s ditch the idea that mental health is about weakness. Getting through hard times, reaching out for help, and working on yourself takes serious courage.

Myth 7: Only People Without Friends Need Therapists

Some people think therapy is just for folks who don’t have close friends or family to lean on. But that’s not really true. Therapy is a totally different kind of support—it’s a place where you can talk openly with someone who’s trained to help you work through things without any judgment or personal ties.

Friends and family are great, sure, but they’re not exactly equipped to handle everything. Therapists, on the other hand, know how to help you get to the root of things in a way that even the best friend can’t. Plus, in therapy, you don’t have to hold back or worry about how it might affect someone else. It’s just you, figuring things out for yourself.

And here’s the thing: therapy isn’t just for people dealing with big crises. Plenty of people go just to work on self-improvement, sort through their thoughts, or get better at handling life’s ups and downs. Whether you’re looking to build confidence, manage stress, or just understand yourself a bit better, therapy can be a huge help.

So, therapy isn’t about lacking friends. It’s about taking the time to work on yourself in a way that friends or family just can’t provide.

Myth 8: Mental Health Problems Are Permanent

A lot of people think that if you’re dealing with a mental health issue, it’s something you’ll just have to live with forever. But that’s actually not true. Many people see major improvements over time, and some even reach a place where they feel completely better.

Recovery isn’t the same for everyone. For some, it means finding ways to manage symptoms well enough to enjoy life, while others might actually see their symptoms go away altogether. Things like the right treatment, a strong support system, and some lifestyle tweaks can make a world of difference.

The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) even says, “recovery is a process, and it’s possible for people to recover and live full and productive lives.” And research backs this up—lots of studies show that with the right help, people dealing with mental health issues often experience big changes for the better.

So, no, mental health challenges aren’t necessarily forever. With the right help and time, many people find themselves in a much better place.

Myth 9: Addiction Is a Lack of Willpower

There’s a common idea that addiction is just a lack of willpower or self-control, but it’s way more complicated than that. Addiction isn’t about being “weak”—it’s a real medical condition that affects the brain.

When someone becomes addicted, their brain chemistry actually changes, especially in areas that deal with motivation and rewards. This is why willpower alone usually isn’t enough to break the cycle. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) explains it well: addiction is “a chronic, relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking, continued use despite harmful consequences, and long-lasting changes in the brain.”

Basically, addiction rewires the brain, making it incredibly hard to quit without help. Studies back this up too, showing that people struggling with addiction benefit most from a combination of treatments—things like counseling, support groups, and sometimes medication.

So let’s throw out the idea that addiction is about a lack of willpower. It’s a complex medical issue, and people deserve understanding and proper help, not judgment.

Myth 10: People with Schizophrenia Have Multiple Personalities

A lot of people mix up schizophrenia with having “multiple personalities,” but they’re actually two completely different things. Schizophrenia is a mental health condition that affects how someone thinks, feels, and perceives reality, sometimes causing things like hallucinations or delusions.

The confusion likely comes from the word “schizophrenia” itself, which loosely means “split mind.” But it doesn’t mean a split personality—more like a disconnect in how emotions and thoughts align with reality. The World Health Organization (WHO) clarifies that schizophrenia is really about distortions in thinking and perception, not multiple identities.

Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), which used to be called multiple personality disorder, is actually the condition where someone has two or more distinct identities or personality states. It’s totally separate from schizophrenia and has its own symptoms and treatments.

Understanding the difference is important, because mixing up these conditions just adds to the misunderstanding and stigma around mental health. Schizophrenia isn’t about “split personalities”—it’s a serious but manageable mental health condition that deserves empathy and accurate information.

Dispelling the Myths, Embracing the Truth

Despite the progress made in understanding mental health, misconceptions continue to fuel stigma and create unnecessary barriers for those seeking support. Recognizing the myths that surround mental health is an essential first step in fostering a more compassionate and educated society. By exploring and debunking these misconceptions, we encourage a shift in perspective, moving away from judgment and toward understanding.

Understanding that mental health challenges are common, multifaceted, and treatable—and that seeking help is a strength—helps build a supportive environment where individuals feel safe reaching out. This transformation starts with each of us, as we challenge the myths we encounter and promote a more accurate view of mental health.

With every myth dispelled, we make room for greater acceptance, empathy, and action. By embracing the truth, we help dismantle the stigma surrounding mental health, paving the way for a world where well-being is prioritized and everyone has the opportunity to thrive.

The Universe

Physicists Suggest All Matter Could Be Made Up of Energy ‘Fragments’

Matter is what makes up the Universe, but what makes up matter? This question has long been tricky for those who think about it – especially for the physicists.

Reflecting recent trends in physics, my colleague Jeffrey Eischen and I have described an updated way to think about matter. We propose that matter is not made of particles or waves, as was long thought, but – more fundamentally – that matter is made of fragments of energy.

From Five to One

The ancient Greeks conceived of five building blocks of matter – from bottom to top: earth, water, air, fire and aether. Aether was the matter that filled the heavens and explained the rotation of the stars, as observed from the Earth vantage point.

These were the first most basic elements from which one could build up a world. Their conceptions of the physical elements did not change dramatically for nearly 2,000 years.

Then, about 300 years ago, Sir Isaac Newton introduced the idea that all matter exists at points called particles. One hundred fifty years after that, James Clerk Maxwell introduced the electromagnetic wave – the underlying and often invisible form of magnetism, electricity and light.

The particle served as the building block for mechanics and the wave for electromagnetism – and the public settled on the particle and the wave as the two building blocks of matter. Together, the particles and waves became the building blocks of all kinds of matter.

This was a vast improvement over the ancient Greeks’ five elements but was still flawed. In a famous series of experiments, known as the double-slit experiments, light sometimes acts like a particle and at other times acts like a wave. And while the theories and math of waves and particles allow scientists to make incredibly accurate predictions about the Universe, the rules break down at the largest and tiniest scales.

Einstein proposed a remedy in his theory of general relativity. Using the mathematical tools available to him at the time, Einstein was able to better explain certain physical phenomena and also resolve a longstanding paradox relating to inertia and gravity.

But instead of improving on particles or waves, he eliminated them as he proposed the warping of space and time.

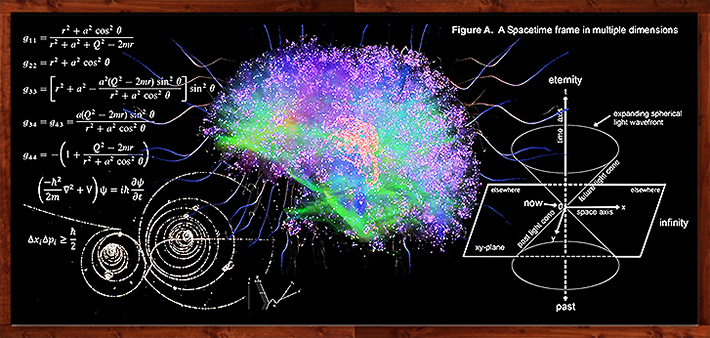

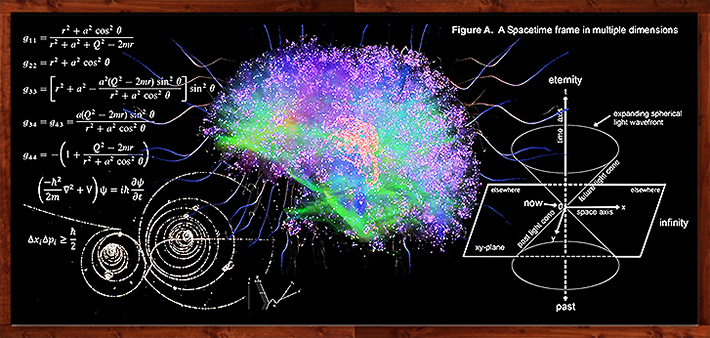

Using newer mathematical tools, my colleague and I have demonstrated a new theory that may accurately describe the Universe. Instead of basing the theory on the warping of space and time, we considered that there could be a building block that is more fundamental than the particle and the wave.

Scientists understand that particles and waves are existential opposites: A particle is a source of matter that exists at a single point, and waves exist everywhere except at the points that create them.

My colleague and I thought it made logical sense for there to be an underlying connection between them.

Flow and Fragments of Energy

Our theory begins with a new fundamental idea – that energy always “flows” through regions of space and time.

Think of energy as made up of lines that fill up a region of space and time, flowing into and out of that region, never beginning, never ending and never crossing one another.

Working from the idea of a universe of flowing energy lines, we looked for a single building block for the flowing energy. If we could find and define such a thing, we hoped we could use it to accurately make predictions about the Universe at the largest and tiniest scales.

There were many building blocks to choose from mathematically, but we sought one that had the features of both the particle and wave – concentrated like the particle but also spread out over space and time like the wave.

The answer was a building block that looks like a concentration of energy – kind of like a star – having energy that is highest at the center, and that gets smaller farther away from the center.

Much to our surprise, we discovered that there were only a limited number of ways to describe a concentration of energy that flows. Of those, we found just one that works in accordance with our mathematical definition of flow.

We named it a fragment of energy. For the math and physics aficionados, it is defined as A = -⍺/r where ⍺ is intensity and r is the distance function.

Using the fragment of energy as a building block of matter, we then constructed the math necessary to solve physics problems. The final step was to test it out.

Back to Einstein, Adding Universality

More than 100 ago, Einstein had turned to two legendary problems in physics to validate general relativity: the ever-so-slight yearly shift – or precession – in Mercury’s orbit, and the tiny bending of light as it passes the Sun.

These problems were at the two extremes of the size spectrum. Neither wave nor particle theories of matter could solve them, but general relativity did.

The theory of general relativity warped space and time in such way as to cause the trajectory of Mercury to shift and light to bend in precisely the amounts seen in astronomical observations.

If our new theory was to have a chance at replacing the particle and the wave with the presumably more fundamental fragment, we would have to be able to solve these problems with our theory, too.

For the precession-of-Mercury problem, we modeled the Sun as an enormous stationary fragment of energy and Mercury as a smaller but still enormous slow-moving fragment of energy. For the bending-of-light problem, the Sun was modeled the same way, but the photon was modeled as a minuscule fragment of energy moving at the speed of light.

In both problems, we calculated the trajectories of the moving fragments and got the same answers as those predicted by the theory of general relativity. We were stunned.

Our initial work demonstrated how a new building block is capable of accurately modeling bodies from the enormous to the minuscule. Where particles and waves break down, the fragment of energy building block held strong.

The fragment could be a single potentially universal building block from which to model reality mathematically – and update the way people think about the building blocks of the Universe.

Republished from TheConversation.com under Creative Commons

Consciousness

Hacker Forms Church to Jailbreak Humanity Out of Our Simulation

(TMU Op-ed) — The Matrix is big money these days. Not the movie so much (although a 4th installment is planned), but rather the Simulation Argument—the idea that we’re living in an advanced computer program or video game.

And the resulting rabbit hole has inspired countless viral articles that accrue major page views all across the web, with the subject itself being debated on prestigious stages by some of the world’s most renowned thinkers and physicists.

Tech magnate and entrepreneur Elon Musk made headlines in recent years when he openly stated he believed we live in a simulation. He was quoted saying he thinks there’s “a one in billion chance we’re living in base reality.” In other words, he thinks it’s astronomically more unlikely that we’re not living in a simulation. He said the game No Man’s Sky further convinced him of this reality. To him, the question is “What’s outside the simulation?”

In a 2017 interview, Musk expanded on his views with a tweet to the Twitter account belonging to the show Rick and Morty:

“The singularity for this level of the simulation is coming soon. I wonder what the levels above us look like.”

The singularity for this level of the simulation is coming soon. I wonder what the levels above us look like.

Good chance they are less interesting and deeper levels are better. So far, even our primitive sims are often more entertaining than reality itself.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) October 5, 2017

Where did such technomanic confidence in a real-life Matrix come from? The original Simulation Argument was penned by Nick Bostrum in 2003, though he started speculating on the end result of a Technological Singularity in 2001. He projected, that with our current rate of technological advancement, it is likely that advanced simulations will be increasingly common in the future, and thus it is likely we are actually in one of those simulations.

When the Simulation Argument first came out I was in college, around the time I already felt like I was living in some kind of dystopian movie in which war criminals could be re-elected to a second term as president and an unstoppable corporatocracy could suck the life and data out of a complacent populace.

Now, 15 years later, it seems we’re at enough inflection point, although this time it’s not just about one issue: with climate change looming, economic collapse imminent, and mindless nationalism seeping back into the global order, it’s as if we’ve hit a cultural singularity of destruction and apocalypse fetishism.

It makes total sense that such a hypothesis would become so popular in this environment. How could this reality be real? It almost makes more sense that this is a simulation. It’s soothing to think this is all some sick experiment by a sadistic posthuman AI or an extraterrestrial youth on higher-dimensional amphetamines and hallucinogens.

But it was hard to predict that such an outlandish concept could become so mainstream that actual scientists were subscribing to it—and actually running experiments to prove it.

However, in recent years, that’s exactly what has happened. A team of German physicists used a field called lattice quantum chromodynamics to create a mini-simulation of a sliver of the universe to see if it has the same kind of arbitrary constraints, such as high energy particles seen in the Greisen–Zatsepin–Kuzmin or GZK cut off.

Theoretical physicist S. James Gate claims to have found a surprising and highly unusual code in his research into string theory. He says that, embedded deep within the most fundamental equations that outline our cosmos, he found self-dual linear error-correcting block code. Essentially, he says there are error correcting 1s and 0s bound up inside the superstrings that constitute the core of our reality. Though Gate was a skeptic on the simulation idea, this discovery shook him.

A new book by Rizwan Virk expands upon Bostrum’s original idea and then takes it to the next level, as he wonders about the nature of our existence within the simulation.

“Probably the most important question related to this is whether we are NPCs (non-player characters) or PCs (player characters) in the video game,” Virk said in an interview with Vox.

“If we are PCs, then that means we are just playing a character inside the video game of life, which I call the Great Simulation.”

Virk argues that the mysterious findings in quantum mechanics—namely that the universe seems to be largely quantum potential and not fixed reality until a human observes it—are consistent with video game rendering logic. “The cardinal rule,” he says, “is the universe renders only that which needs to be observed.”

The cultural influence is significant, too. As we careen toward a frighteningly uncertain future, the temptation to engage in newer, proto-technologist forms of escapism grows stronger. The downstream effects of the Simulation Argument are becoming more clearly defined as a traditional religious psuedo-science, with YouTube videos of people claiming you can hack reality and reprogram your mind to live in the universe of your choosing.

One hacker, George Hotz, is so convinced we’re living in a simulation that he’s created a church for it, his goal being to figure out how to hack the simulation and escape into a new reality.

“It’s easy to imagine things that are so much smarter than you and they could build a cage you wouldn’t even recognize,” George stated, adding that the solution is to “jailbreak the simulation,” and either meet our makers or destroy them.

It’s hard to say whether such ideas are productive or dangerous. It’s unlikely Bostrom—who claims he had not seen The Matrix before writing his seminal paper on the hypothesis—could have ever imagined his idea would become so firmly embedded in the zeitgeist. He also likely could not have imagined the all-encompassing, dystopian nature of the surveillance grid we would live in nearly twenty years later.

People increasingly feel like they’re losing control of not only their own realities, but the collective, consensus reality we live in. It’s enticing to believe there’s a larger mystery governing the laws of this insanity. It’s enticing to view consciousness as some kind of reality-hacking, non-biological buzzsaw slicing through the quantum ether.

But at the end of the day, perhaps our minds are just the unlikely interfaces between chaos and energy. Given the unlikeliness of existing at all, maybe that should be enough.

Consciousness

How to Leverage Your Own Conscience as Pure Law

“Highly evolved people have their own conscience as pure law.” ~Lao Tzu

If we heed these wise words by Lao Tzu, then it stands to reason that we focus more on developing highly evolved people capable of honoring universal laws, rather than waste our energy bludgeoning people with invalid laws that violate the golden rule, the nonaggression principle, and the universal laws that dictate health.

But what constitutes a highly evolved person? What might a highly evolved person’s character look like? How do we define such a broad concept? In Five Counterintuitive Traits of Highly Evolved Humans, I broke down the emotional disposition of highly evolved people. In this article we’ll break down the political disposition of highly evolved people.

Choose a courage-based lifestyle over a fear-based lifestyle:

“A government which will turn its tanks upon its people, for any reason, is a government with the taste of blood and a thirst for power and must either be smartly rebuked or blindly obeyed in deadly fear.” ~John Salter

Does your government have a taste for blood and a thirst for power? A highly evolved person, with their own conscience as pure law, would choose smart rebuking over fearful obsequiousness.

Don’t allow such a government to have its way. Question its authority. Practice strategic civil disobedience. Count coup on overreaching power constructs. Challenge outdated, immoral, and unjust laws. Be the personification of checks and balances. Dare to be a courageous David facing down the Goliath of the state.

We don’t need more people who blindly obey in deadly fear. That’s already the vast majority of people. We need more people who are highly evolved enough to smartly rebuke any and all governments that use violence to “solve” problems.

Choosing a courage-based lifestyle over a fear-based lifestyle is choosing to no longer be a victim. It’s choosing, instead, to become a hero. It’s choosing courage over fear, self-sacrifice over comfort and security, adventure over banality, fierceness over obsequiousness, and ruthless skepticism over blind faith.

Understand that the vast majority of people are still willing to live fear-based lifestyles. Sympathize with them for having not woken up yet, but do not pity them. It’s not their fault they were brainwashed, conditioned and indoctrinated into living fear-based lifestyles, but it is their responsibility to educate themselves and to break themselves of their conditioning.

You can lead people to knowledge, but you can’t make them think. You can, however, remain ruthless with your courage-based lifestyle. Become a beacon of courageous hope. Especially for those who are still living fear-based lifestyles. Call it tough love. As Derrick Jensen said, “Love does not imply pacifism.”

Choose heart-centeredness over political divisiveness:

“We want to abolish the state and create a world free of oppression and suffering, but we must not lose sight of ourselves in the pursuit of this goal. Remain heart-centered no matter how violent the state becomes or how divisive the political climate. Every revolutionary through history who chose violence became a monster and a shadow of what they pursued. Remember, we are after an evolution of hearts and minds.” ~Derrick Broze & John Vibes

Bipartisan politics is old hat. It’s high time you toss that hat in the fire. Highly evolved people have already done so. They have gone Meta with politics. They’ve gone beyond the outdated, codependent divisiveness of bipartisanism and graduated into an updated, interdependent metamorality.

Metamorality, coined by Joshua Greene, is based on a common ground that all humans can agree upon while proposing a utilitarian deep pragmatism that empathically broadens the mind and compassionately opens the heart to the plight of us all as interdependent beings on an interconnected planet. Highly evolved humans use this strategy, along with the Astronaut Overview Effect, to go big-picture.

Going big-picture helps us change our minds. Or, at least be more flexible and open in our thinking. It puts things into proper perspective. It helps us feel more empathic and less psychopathic toward each other. We’re better able to see the world as one, without borders.

We’re better able to narrow our highfalutin politics down to a single concept we can all agree on: freedom. We’re better able to see through all the red herring cognitive biases of the climate debate and realize that our problem is a single problem we can all agree on: pollution. We’re better able to cut straight through the divisiveness of religion and narrow it down to a single concept that we can all agree on: love. Especially love for our children, and creating a healthy environment for them to grow up in. And suddenly there are not so many differences between us.

Choosing heart-centeredness over political divisiveness puts a compassionate spin on our conscience. Indeed, it puts the “conscience” in having our own conscience as pure law. For pure law is universal law, based upon the healthy interconnectedness of all things.

Choose self-improvement over self-preservation and create a better world:

“You are personally responsible for becoming more ethical than the society you grew up in.” ~Eliezer Yudkowsky

When it comes down to it, becoming a highly evolved human is about spitting out the unhealthy blue pill of comfort, safety, and security based on outdated laws, and having the courage to swallow the healthy red pill of curiosity, questioning, and skepticism that questions bad laws in order to create healthy laws that align with universal laws.

It’s about becoming the personification of checks and balances. It’s about putting in the hard and difficult work of becoming a highly evolved person who has the wherewithal to “use their own conscience as pure law.” And to teach others how to do the same.

The answer is not creating more bad laws to shove down people’s throats. The answer is creating people smart enough to question the authority that seeks to shove bad laws down people’s throats. Indeed. The answer is teaching people how to become bigger than the law, how to gain the capacity to have their own conscience as pure law, and how to become a more valuable human. As Niels Bohr said, “Every valuable human being must be a radical and a rebel, for what he must aim at is to make things better than they are.”

If, as Plato famously said, “Good people do not need laws to tell them to act responsibly, while bad people will find a way around the laws,” then it stands to reason that we should focus more on teaching people how to act responsibly and less on creating laws. Especially since humans are so terrible at making good laws. And especially-especially since humans are even more terrible about abusing their power regarding those ill-conceived laws.

As Edward Abbey wisely suggested, “Since few men are wise enough to rule themselves, even fewer are wise enough to rule others.” The few seeking to rule others do so through the enforcement of bad laws.

So, it is incumbent upon anyone with their own conscience as pure law to ruthlessly interrogate such bad laws and then mercilessly check and balance any authority seeking to enforce such bad laws. We do ourselves, our children, and our grandchildren a disservice when we decide not to.

There is no greater cause than becoming more ethical than the society you grew up in. Will you defend outdated unethical laws and merely turn a blind eye to those who unjustly enforce them? Or will you defend the people’s right to ruthlessly challenge unethical laws and those who unjustly enforce them? The choice is yours. As William James said, “We are all ready to be savage in some cause. The difference between a good man and a bad one is the choice of the cause.”

Consciousness

Shedding Outdated Skin: Building the Bridge from Man to Overman

“The snake which cannot cast its skin has to die. As well the minds which are prevented from changing their opinions; they cease to be mind.” ~Friedrich Nietzsche

If you would be alive –if you would choose to live an examined life, a fulfilled life, a self-actualized life, a life well-lived– then don’t fearfully choose the safe road, what Jung called “The Road of Death.” Choose instead the courage to face the trials and tribulations of an adventurous road, a road full of danger and risk.

On the bridge from Man to Overman, there is no place for half-assed lifestyles and herd instincts. There’s no place for fear-based perspectives and cowardly excuses. There’s no place for play-it-safers and goodie-two-shoes clinging to comfort and light. The bridge is too narrow for narrow-mindedness. It’s too shadowy for those who have not reconciled their own shadows. It’s too full of dark nights for anyone who hasn’t experienced a Dark Night of the Soul. It’s too painfully real for those who have not overcome the Matrix and embraced the Desert of the Real.

The bridge is only for courageous self-actualizers and heroic self-overcomers. If your intent is not self-actualization and self-overcoming, then simply get out of the way. Don’t block those with a full heart just because your heart is empty. Better yet: fill your heart with courage. Join the ranks of healthy progressive evolution. “I teach you the Overman,” writes Nietzsche. “Man is something that should be overcome. What have you done to overcome him?”

Taking the leap of courage:

“Every valuable human being must be a radical and a rebel, for what he must aim at is to make things better than they are.” ~Niels Bohr

Can you feel the constriction of your comfort zone? Like a heavy life-jacket weighing you down? Like a too-safe straight-jacket keeping you out of harms way?

Can you feel the warm glow of contentedness quietly stagnating you? Causing you to feel like you’ve made it somehow? Can you feel the secure pressure of the status quo keeping you in line? Causing you to blindly accept, to myopically believe that you’ve somehow got it all figured out?

Taking a leap of courage is daring yourself to escape these feelings. It’s encouraging yourself to step outside your comfort zone. It’s having the audacity to think rather than believe, to take things into consideration rather than rely on conviction. It’s inspiring yourself to be heroic despite fear.

Look, I get it. Inside the comfort zone everything is safe and warm, solved and unriddled. But there’s also no adventure there. There’s no risk. There’s no challenge. There is everything in there to help you heal, it’s a great place to lick your wounds, but there’s nothing there to help you grow.

Healthy growth, the kind of growth that builds resilience and robustness, can only be achieved outside the comfort zone. There’s got to be risk. Like Nietzsche said, “Man is a rope, tied between beast and Overman – a rope over an abyss. A dangerous across, a dangerous on-the-way, a dangerous looking-back, a dangerous shuddering and stopping.”

Inside the comfort zone there’s placation, pacification and pity. There’s everything that keeps us appeased and satisfied. There’s God with his shiny promises and glossy platitudes keeping us pampered and coddled and giving us that warm fuzzy feeling. But there’s no growth. There’s no questions. There’s no humor. There’s no furthering of evolution.

Outside of the comfort zone God is dead. Or, at least, God is a garden. A vast and vital garden filled with the compost of every man-made God to ever have existed, rotting like deified fertilizer for the future fertilization of ever-improved and ever-updated Gods.

Alas, the bridge from Man to Overman can only be built outside our comfort zones. Building the bridge is building adventure. It’s building something to grow into. It’s rebuilding God. It’s building a path into godhood and creative evolution. Indeed, we stand upon the corpse of God in order to self-actualize our place as Gods in the making.

Building the bridge out of the bones of God (and Giants):

“We are all Mothers of God, for God is always needing to be reborn.” ~Meister Eckhart

The bridge is a symbol for revivification, a creative renaissance, a spiritual rebirth, an existential resurgence. The bridge is a path, but it’s also a crossroads –a snarling juxtaposition. It’s built out of the outdated bones of God toward the updated end of creative evolution. It’s fixed into place with existential glue. It’s sturdier than any bridge ever created, but it’s surrounded by an angry abyss, and it’s never completed.

We are all architects of this bridge to some extent. Some of us are aware of it, but most of us are not. Most of us are cluttered and stuck in stopgap ideologies. We’re clustered and bottlenecked before the crossroads. Unable to self-actualize. Unable to self-overcome. Unable to see how everything is connected to everything else. Like pre-enlightened Rumis, we’re incapable of seeing that the door to our prison is wide open. And always has been.

Building the bridge from Man to Overman is proactively engaging and leveraging open-mindedness through self-actualization and self-overcoming. It’s inflicting awareness. It’s launching existential flares. It’s highlighting creative evolution through courageous interdependence.

The bones of God are sturdy and steadfast. Solid ground upon which to keep moving, ever-forward, ever-overcoming, ever-evolving. It takes the Newtonian notion of “standing on the shoulders of giants” to the next level. It’s Meta-perceptual. We stand on the bones of God in order to see further than God did. In order to perpetually propel human imagination and ingenuity. In order to grow and keep growing, despite creature comforts, herd instincts, and psychosocial hang-ups.

Building the bridge begins with each of us taking personal responsibility for our contribution to human evolution. Indeed. We all carry the bones of God. Self-overcoming is taking the reins of our life into our own hands, and proactively going about improving upon who we were yesterday. It’s a personalized Fibonacci sequence (self-improvement) striving toward Phi (enlightenment), where our own development is predicated upon an individualized progressive evolution that will ultimately contribute to the evolution of the species.

If you meet Nietzsche on the bridge, kill him:

“If you meet The Buddha on the road, kill him.” ~Linji

As Zen master Shunryu Suzuki wrote in Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, “Kill the Buddha if the Buddha exists somewhere else. Kill the Buddha, because you should resume your own Buddha nature.” Similarly, we should kill our notion of self-mastery in order to continue improving our mastery. Think of it as a kind of recycled mastery, where we recycle the mastery of yesterday into the remastered mastery of today.

This applies to the concept of deification itself. So as not to get stuck in a particular state of growth, it is vital that we “kill” the notion that we have “arrived.” That our evolution is somehow “complete.” That there is nothing further to grow into, nothing to question, nothing to overcome. For there will always be something to grow into, to question, and to overcome. There will always be a vast infinity toward which our limited finitude must strive. Indeed. The bridge from Man to Overman is built ever-finitely into the infinite future.

Killing Buddha (God) on the road and killing Nietzsche (Godhood) on the bridge is vital to keep creative evolution in perspective, so as not to get hung-up on any particular notion of Truth. The bridge from Man to Overman is filled with the outdated bones of dead Gods and the burnt-out husks of outdated truths. As James Russel Lowell said, “Time makes ancient good uncouth.”

Those who are proactively and courageously building the bridge understand that Truth is a fickle beast. Almost as fickle a beast as human fallibility. It’s for both reasons that those who are building the bridge consistently recycle their own mastery.

At the end of the day, the bridge from Man to Overman is a process of self-actualization and self-overcoming. It’s the collective personification of creative evolution. We build the bridge to provide a flexible and malleable path toward godhood. We keep building, destroying and rebuilding so that past growth adds to, without subtracting from, the healthy and progressive evolution of the species. We stand and face the Abyss, honoring each other… “Overmaste: the (r)evolutionary potential in me honors the (r)evolutionary potential in you.”

Image: Source

Consciousness

Practice this 3-Minute Breathing Exercise to Get Calm in Any Situation

(TMU) – Life abounds with stress-making, havoc-provoking mayhem. Did you misplace your keys when you were already late for work this morning? Was traffic worse today than after a 5-car accident on a Los Angeles turnpike? Is your boss expecting the impossible from you, while you stare into your kid’s eyes and choke back tears explaining you’re going to have to miss their game – again?

In these moments, you need a fast, effective method to chill the heck out. This simple exercise can calm you down and eliminate stress in three minutes or less.

A Stealth Breathing Technique Used by Navy Seals and First Responders

The best thing about this breathing technique is that no one will even know you’re doing it.

It is used by first responders, Navy Seals, and people who are regularly under massive amounts of stress because it has a direct, palpable, and positive effect on the way their nervous systems function.

If you were to pick someone up in an ambulance from one of those LA traffic pile-ups, you don’t have time to freak out. Maybe they won’t live. You have seconds sometimes, to make smart choices that could possibly keep them breathing long enough to get them to a hospital.

Every fiber of your being has evolved over time to signal danger. This is part of your body’s fight-or-flight response.

Counter-Acting the Fight or Flight Response

When faced with danger or any perceived threat, you instinctively default to two choices: run or fight.

A cascade of chemical reactions occurs the minute a stressful situation presents itself. This is how the body mobilizes its resources to deal with a threat. It doesn’t matter if it is a lion about to pounce on you – as our ancestors had to deal with – or that one last email that finally breaks you. Your natural response to stress will be the same – until you learn how to interrupt it.

The sympathetic nervous systems will trigger the adrenal glands to release catecholamines, which include adrenaline and noradrenaline. This causes your heart to pound, your blood pressure to rise, you’re your breathing rate to speed up.

Your pupils may dilate, and your skin may flush. In extreme stress, your muscles tense up – literally preparing you to run away from the dangerous trigger.

Modern-day triggers are so varied and pervasive, we are almost never in a state of calm.

After a stressful event, it can take up to 45 minutes for your body to return to homeostasis.

That’s why a simple breathing exercise can literally save your life, and retrain you to face stressful situations like a seasoned, meditating monk instead of a raging lunatic.

Cynthia Stonnington, chair of the department of psychiatry and psychology at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, Arizona, says she introduces people to breathwork because “many people find benefit, no one reports side effects, and it’s something that engages the patient in their recovery with actively doing something.”

Breathwork is in fact, so useful, that one study published in the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine in 2017 found that patients with major depression who practiced deep breathing methods for three months had significantly reduced symptoms as compared to those who did not.

Another study found that our breathing is so closely linked to our emotional state, that changing it can practically negate anxiety completely.

How it Works

Sometimes called box-breathing, you can really use any form of deep, present and conscious breathing to change your physiological response to stress.

Most of us breathe in an unconscious, stress-promoting way. Here’s what happens when you breathe deeply, and correctly for just a few minutes:

- An exhale that is longer than your inhale (deep breathing) causes the vagus nerve which runs from the neck down through your diaphragm to relay a message to your brain to turn up your parasympathetic nervous system and turn down your sympathetic nervous system – the part of your nervous system responsible for rest, relaxation, peace, and digestion.

- This counter-acts the adrenal-dump and flight or fight response.

- Your brain is freed to make smart choices based on relaxed concentration, a state known as Alpha that is seen on EEG scans as neural oscillations in the frequency range of 5–12.5 Hz arising from synchronous and coherent (in phase or constructive) brain activity.

- Alpha waves caused by a deep-breathing pattern create a positive feedback loop that restores harmony between your mind and body.

- This brainwave state is also indicative of those “aha” or “eureka” moments of a compelling new idea, or insane creativity. They allow you to literally create something out of nothing. And when do you need to do that most often? When you are faced with a challenging or stressful situation!

How to Do It

You can start with a box breath and expand into larger inhale-exhale ratios.

A box breath is a simple inhale to the count of four, using your diaphragm. You then exhale for a slow count of four.

Be sure you expand your lungs completely, and fill them as much as you can. If your shoulders are shrugging into your ears, you are likely doing a “stress-breath” which only keeps you in the fight-or-flight stage. This is a shallow breath that we normally do when we are agitated or depressed.

Your stomach should expand, not just your lungs. This is because your diaphragm is moving down into your belly to allow your lungs to expand more fully.

Once you can do this, you will change the ratio. You will start with a 4:8 inhale to exhale ratio, and then move to 8:16, 10:20, 22:44, or even 30:80 etc.

If you want some real inspiration for deep breathing, check out this video of the famous yogi, B.K.S. Iyengar, conducting one of the longest exhales ever.

You don’t have to be this advanced to get all the benefits of deep breathing, though. Simply have enough awareness to take control of your breath the next time a stressful situation arises, and you’ll be feeling less anxious, and calmer.

It’s that simple. You can breathe yourself into peace, in three minutes or less.

Consciousness

Stranger Psychic Phenomenon Than Déjà Vu? Its Déjà Rêvé

Déjà vu, the phenomenon of feeling like you’ve already experienced something before – a smell, a room, someone’s presence, even though you don’t have a conscious memory, is something that reminds us that the world of consciousness is a little more flexible than we often assume. Déjà Rêvé is even stranger. This weird anomaly of consciousness happens when you recall dreaming something at the exact same time that you see it in “real” life. Are these psychic phenomenon indicators that time, space, and consciousness are more like a stretched rubber band, rather than the linear staircase of events and neurological firings that we are taught to believe?

Déjà Rêvé translated from the French means “already dreamed.” It’s a form of precognition that many people have experienced – just like déjà vu. Or, is it just another trick of the mind?

Freud, Jung and the Subconscious, Unconscious & Superconscious Mind

Before we dive a little deeper into déjà rêvé and déjà vu, among many psychic phenomenon, it is helpful to understand some of the prevailing models of the mind.

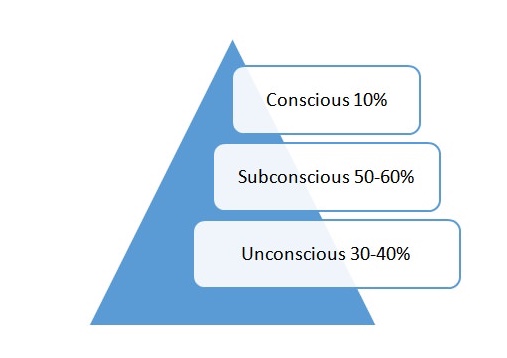

Psychologist, Sigmund Freud, for instance, imagined in the 1900s that our minds contained information divided into three groups:

- The unconscious mind: 30 – 40%

- The subconscious mind: 50 – 60%

- The conscious mind: 10%

Image: journal psyche.org

Closely related to Freud’s concept of mind is Carl Jung’s, since he was taught by Freud, and later diverged from some of Freud’s theories to develop his own. Jung estimated that our mind is divided further into another category he called the Superconscious Mind. This has also been called the “Collective Unconscious,” “Divine Mind,” “One Mind,” “The Source,” or even “God.” It essentially represents Infinite Wisdom, or the organizing force which creates all of the Universe – which we so often forget that we are not just a part of, but that we ARE.

Jung did extensive research on dreams, memories, and reflections, including precognitive or psychic experiences, including déjà vu and déjà rêvé.

Distinguishing Between a Precognitive Dream and Déjà Rêvé

Let’s look closer now at the distinctions between these psychic (or simply consciousness) phenomenon. Déjà rêvé is when you have the sense that you have dreamed something before, when it is happening in real life, even though you don’t recall a specific instance of being somewhere, doing something, or talking to a specific person.

This is slightly different than a precognitive dream. In a precognitive dream, you simply dream of something that indicates an instance of interaction or experience in the future, and then you later experience that very same “cognitive” act in real life – so the dream told you what would happen before it did.

Examples of this abound in human history. As Ian Wilson explains in a paper on Déjà rêvé,

“President Abraham Lincoln, weeks before his assassination, dreamt of his death. Author Mark Twain had a dream involving the death of his brother Henry weeks before Henry would die in a riverboat accident, with remarkable and uncanny detail in regard to the funeral that followed. British painter David Mandell dreamt three times of planes crashing into the twin towers. In 1996 he painted a picture of such a dream and had it time-stamped in a photograph using his bank’s clock. . .”

Some studies indicate that déjà rêvé is not a psychic experience, but a trick of the mind. In a recently released paper titled Déjà vu: An Illusion of Prediction, cognitive psychologists from Colorado State University explain that déjà vu is simply a memory phenomenon — one that can be recreated in a lab. The abstract explains,

“Despite recent scientific advances, a remaining puzzle is the purported association between déjà vu and feelings of premonition. Building on research showing that déjà vu can be driven by an unrecalled memory of a past experience that relates to the current situation, we sought evidence of memory-based predictive ability during déjà vu states. Déjà vu did not lead to above-chance ability to predict the next turn in a navigational path resembling a previously experienced but unrecalled path (although such resemblance increased reports of déjà vu). However, déjà vu states were accompanied by increased feelings of knowing the direction of the next turn. The results suggest that feelings of premonition during déjà vu occur and can be illusory. Metacognitive bias brought on by the state itself may explain the peculiar association between déjà vu and the feeling of premonition.”

However, other studies have a different take on experiences like déjà vu and déjà rêvé.

Dr. David Ryback also conducted a survey in his publication “Dreams That Came True” with an 8.8% frequency with regards to precognitive dreams. Ryback has also suggested that we can alter reality by having lucid precognitive dreams. He even puts forth that physical reality is a dream-training simulator.

Even philosopher Aristotle skeptically debated precognitive dreams in his paper written in 350 BCE called, “On Prophesying by Dreams.”

What is startlingly strange with déjà rêvé though is that they seem to have a direct and relative relationship with physical reality. If this is true, we need to start asking bigger questions – like what are the origins of “reality”?

Reality Can Be Altered with DreamTime

When we couple this emerging information with the latest advances in quantum physics, we can start to understand how all psychic experiences are quite probably just an expansion of our abilities to alter reality, and to experience it in multiple time-frames. If time isn’t real, and “reality” can be altered with our dreamtime, then who is to say that we haven’t all experienced everything before, and therefore have dreams of being somewhere before or having the very same conversation with a friend?

Ancient tribes from Australia to North and South America, and all across the globe are familiar with “Dream Time.” They knew that the world is not the “thing,” and therefore we can change it with our consciousness.

An acknowledgement of something beyond Cosmic time, and the acceptance of Infinite Consciousness change everything. Scientists can say that déjà vu and déjà rêvé are tricks of the mind, but it is possible that they are the results of expanding consciousness – and a direct link to Jung’s Superconscious Mind.

Image: stefano carniccio/Shutterstock.

Consciousness

A Zen Master Explains the Art of ‘Letting Go’, And It Isn’t What You Think

Thich Naht Hanh, the Zen Buddhist master, has some interesting advice about what it means to truly let go. Many people mistake detachment or non-clinging to be a form of aloofness, or emotional disconnect from others, but as Hanh explains, truly letting go often means loving someone more than you have ever loved them before.

The Buddha taught that detachment, one of the disciplines on the Noble Path, also called ariyasaavaka, is not a physical act of withdrawal or even a form of austerity. Though the Buddha teaches of a “non-action which is an integral part of the Right Way,” if it is taken out of context it can give the impression that we should develop a lack of concern for others, and that we should live without truly feeling or expressing our emotions – cutting ourselves off from life.

These type of misinterpretations are sadly common, since there are not always direct translations from the Paali language into English.

This form of “detachment” is an erroneous understanding of the Buddha’s message. Master Hanh states that to truly let go we must learn to love more completely. Non-attachment only happens when our love for another extends beyond our own personal expectations of gain, or our anticipation of a specific, desired outcome.

Hanh describes four forms of complete detachment, which surprisingly, aren’t about holing yourself up in a cave and ignoring everyone who has broken your heart, or ignoring your lust or desire for a romantic interest. This is not detachment. Letting go, means diving in. For example:

Maitri (Not the Love You Know)

Hanh describes the importance of Maitri, not love as we normally understand in a Westernized use of the word. He states,

“The first aspect of true love is maitri (metta, in Pali), the intention and capacity to offer joy and happiness. To develop that capacity, we have to practice looking and listening deeply so that we know what to do and what not to do to make others happy. If you offer your beloved something she does not need, that is not maitri. You have to see her real situation or what you offer might bring her unhappiness.”

In other words, your detachment may come in accepting that certain things you would normally do to make another person feel loved and appreciated may not be what the person you are actively loving now, needs. Instead of forcing that behavior on another person, with an egoic intent to “please” them, you simply detach from that need in yourself, and truly observe what makes another person feel comfortable, safe, and happy.

Hanh further explains,

“We have to use language more carefully. “Love” is a beautiful word; we have to restore its meaning. The word “maitri” has roots in the word mitra which means friend. In Buddhism, the primary meaning of love is friendship.”

Karuna (Compassion)

The next form of true detachment is compassion. When we let go, we don’t stop offering a compassionate touch, word, or deed to help someone who is in pain. We also don’t expect to take their hurt or pain away. Compassion contains deep concern, though. It is not aloofness It is not isolation from others.

The Buddha smiles because he understands why pain and suffering exist, and because he also knows how to transform it. You become more deeply involved in life when you become detached form the outcome, but this does not mean you don’t participate fully – even in others’ pain.

Gratitude and Joy